Working as a Software Developer* in a range of small companies and organizations, I’ve had the opportunity to work on quite a number of different projects. That experience has given me a healthy appreciation for how not to execute projects, as well as a healthy respect for process. Recently I pulled together a basic process to help manage the development tasks I am working on, track completion against my estimates, and a number of other things. It takes roughly an hour every two weeks and 5-10 minutes per day to maintain.

This isn’t a new process or even a sales pitch on how you too can implement my process and save thousands. It’s simply a walk through of the challenges that led to the process, the tools and practices I incorporated, and the steps I followed to build a lightweight process.

*Software Developer: It seems every developer position I’ve held has had a different definition of ‘Developer’ (and ‘Programmer’, and…you get the point). The positive side of this is lots of great experiences, the negative side is all the fun things I got to use/do and never again.

Building a Process

Just as we do (or should do) when building software, we need to have a purpose. Often the largest, clumsiest processes occur through a lack of focus or a desire to focus in every direction (ultimate flexibility, no limits, etc). That lack of focus leads everyone to add their own bits to the mix. One person adds what worked in his last project, someone else adds something she always wanted to try, more pieces are added to cover ever eventuality or risk that can be thought of….and Colossus is born, moving so slowly that all involved often think they are moving backwards and could be beaten by a 2 man team in a garage.

The purpose of process is to provide consistency and ground rules. A good process is an enabler.

I know, that sounds odd (and many of you probably think you are totally against having any process), so lets try a comparison.

Say we’re working on a software development project and we are required to deliver code documentation as part of the project. Once upon a time this would have required a great deal of time to put together, keep up to date as changes occurred, etc. It probably would have been a full time job on any team over 3-4 developers. Then someone came along and said “Look, if we comment every function like so, then I can write a script to extract those comments and automatically build the documentation.”

In the software world we call this a “convention”. Incorporating conventions into our practice allows us to automate or get some extra value out of something simply because it’s been done in a consistent manner (possibly with an extra step or two sprinkled on top).

Process is not inherently bad. Like writing software, there is never only one answer and even using the latest and greatest of tools you can build a ghastly, unmaintainable mess.

So Back to My Process

So recently I started the new job and I was given responsibility for adding some new capabilities to a system. I had the freedom to define my own processes, determine how I was going to get the work done, and so on. The critical deliverable was only delivery of working software, added in a manner not inconsistent with the existing platform.

My focus for the process is:

- Know as far ahead of time as possible if I was diverging from initial estimates

- Collect just enough data to re-estimate completion if order of tasks changed, interruptions occurred, etc

- Have a sense of accomplishment, see the work getting done

- Have a way to track how much of my time is spent on interruptive tasks, scope additions, etc

So this is my bare minimum set of requirements from my process, my focus.

Then we have some challenges:

- High potential for variability/change

- I am new to the company and have a poorer feel for what they need than more experienced employees

- The company hasn’t had this type of system before, so the requirements will be more changeable and will require greater refinement along the way

- I don’t have direct contact with stakeholders or end users

- Limited experience with tools (existing, in-house architecture/codebase)

- I am not comfortable (or was not) with the system I was adding onto

- Standards are limited to finding existing examples to duplicate

- Expected to convert some existing components for wider use w/ my portion without disrupting their existing functions

- No automated testing – the framework is challenging for unit testing

- Live environment – though my pieces of the system would not be live for weeks or months, the system is deployed weekly and existing portions would be used and revised

- I am a team of one – limits flexibility, easier to get “stuck in the mud” without someone to pull me out, limited to my own experiences

So having a focus and an understanding of my initial challenges, I built an initial process.

The End Process

From the focus and challenges above, I pulled together a minimal process. Let’s look at that process then circle back around to the “why was that piece chosen”. This process borrows heavily from Lean and Scrum processes, incorporating the idea of iterations (or sprints), a visual board, and a burndown chart.

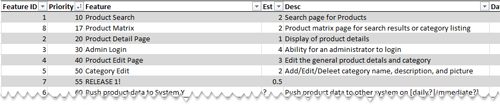

I started by identifying the major features we were looking for in the system. Once I had these (through a series of conversations and prototyping), I had my manager prioritize them and help group them into potential releases. Initially this proved to be 3 major releases and a few extra features that would be prioritized after the last release.

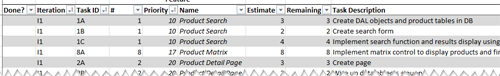

I put all of these features into a spreadsheet, along with their priority and a rough estimate in ideal days. In a separate page of the spreadsheet I broke down each of the features into individual tasks and estimated those tasks in hours. There was a little variance between my individual task estimates and the feature estimates, but they averaged out.

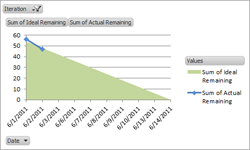

In a third tab, I created a list of the available workdays for the project, an iteration code, a number of hours available for each day (initially 6), a calculation for number of hours remaining in the iteration, and an empty column for the number of task hours remaining. I then created a pivot chart for this table, grouping by the iteration so I could easily display a burndown chart of the expected hours being done against the actual tasks being completed.

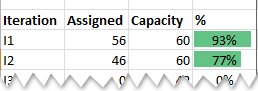

The last spreadsheet step was to load up my first iteration without overloading myself. Adding an iteration code to my task list tab and some calculated fields (visible in the task spreadsheet screenshot above) let me total up how many estimated hours I was loading into the iteration.

Simple graphs of available capacity vs assigned tasks

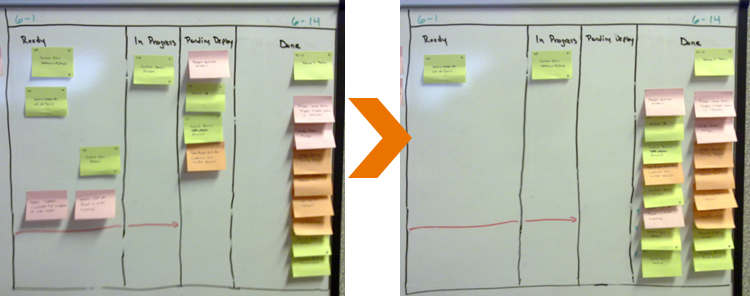

After setting up the spreadsheet, I setup a visual board in the corner of my whiteboard. I created columns for tasks that were ready to be worked (tasks assigned to the current iteration), tasks in progress, tasks completed and waiting for the weekly deployment, and tasks that were completed and in the live environment. Within a couple days I also added an express lane at the bottom for bugs and high priority feature revisions.

Pictures of visual board over time

The sticky notes were kept fairly simple. The color indicates the type and each has the name of the task and the iteration code written on it. Though I did not implement WIP limits (Kanban) on my columns, I have unofficial numbers in my head to help me limit task switching.

As the iterations progress, I calculate how many estimated hours of work I get done per day and update that value in the third tab of my spreadsheet. This ratio of estimation hours to real hours then helps me project forward and see if I am on track for the final release, need to refine some tasks to reduce their estimated time, or potentially have some time to pull in tasks at the end.

How I Got Here

So I started with a focus and some challenges and ended up with all of that (which is actually a fairly lightweight process, it just took a lot of space to write it up). Here’s the connections:

Why Iterative?

I chose to use an iterative process to help manage the risks for variability and my own limited experience. An iterative process would help me course correct far sooner and take advantage of my growing experience in the company and with the software instead of trying to base the entire project off of my knowledge on day one.

So the iterative process was chosen to help reduce the impact of risks involved with my knowledge of the software and my understanding of the requirements, as well as refinements that were expected to occur along the way.

Why a spreadsheet? Why estimated hours?

I chose to use a spreadsheet and this method of estimated vs real hours to address measurement of actual execution against estimated and provide an ability and data to re-estimate tasks as time progressed.

Can I have your spreadsheet?

Below is a link for the sample workbook I put together for the images in this post. Being an example, it hasn’t actually gone through the process of being used, revised, marked up, etc like the actual one I use.

It has no instructions, no notes, and is in XLSX format.

Why such small tasks?

Why did I break down the features at all? They’re only a few days worth of work, couldn’t I have just used those?

Well yes and no. By going with smaller tasks I can usually move one or two tasks from doing to done in any given day, which feeds back into my feelings of productivity and such. Smaller tasks also help me find out I’ve gone off the rails sooner or that I missed something critical. Additionally, smaller tasks are easier to move around, if I intend to do task 1A-1C but a bug comes in, I can wrap up my work on 1A, do the bug, then come back to 1B with a much lower task switching cost then if I was switching inside feature 1.

Small tasks also feed back into estimates, force us to evaluate the features more deeply, bring future issues to the surface early enough that we can start asking questions before we get to do-or-die time, etc.

Seriously, Sticky Notes?

I chose the visual board for several reasons. The first is that seeing the work flow across the board helps give me a sense of accomplishment. Good morale and a sense of accomplishment help keep me from getting bogged down or feeling like I’m not making progress. The visual board also gave me a way to see the level of revisions that were occurring and the impact they were having as the iteration progressed.

The final advantage was that the board reduced the time it took me to switch tasks, at any time I could glance at the board and see what I was working on last, what I would likely be working on next, etc. When I go into work after a 3 day weekend, it will take me longer to boot up my computer than to determine what I was working on. I also have a visual of how many tasks I am trying to work on simultaneously, and that causes me to try and limit that number, reducing task switching. In Lean terms, I have reduced my changeover time, some of the waste involved in those changeovers, and the number of changeovers that occur (splitting releases into features into smaller tasks also reduced my batch size).

What’s Missing?

The only challenges that my process did not address were a method to limit the risk of working on live software without a safety net (other than manual testing). I did address this, but that’s probably for another post.

Wrapping Up

The most critical part of creating a process is to know why your creating it. Without a focus, without knowing the goals and risks, you run the risk of creating something that costs more than it solves. Like programming or any other skill, selecting and building a good process is easier the more you do it. Pay attention not just to what does work, but also to what doesn’t. My process is not perfect and it will have failures, I intend to learn from them. But I’m also learning from the processes I see others following.

If you are interested, here are some random links on related topics (plenty more in my Delicious bookmarks).

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.