This is the second article in a multi-article set that describes the basics of Kanban and explores applying Kanban to IT Processes. Part one provides a basic overview of Kanban and how it is used in manufacturing. The remaining parts explore sample scenarios to help generate ideas for your own environment.

In this, part 2 of the “Applying Kanban to IT Processes” series, we are exploring a generic help desk environment and how Kanban helps them improve their image, measurability, morale, and task reaction and completion times. The example boards and processes in the article are not intended to be drop-in process changes for your business, but instead are designed to walk through a process of creating a Kanban-based system and applying it in a fictional setting. As Kanban is a philosophy and not a fixed set of processes, please remember that this is just one example of how it could be applied in the selected fictional setting.

Welcome to ABC Corp’s Help Desk

This story follows the fictional help desk group for ABC Corp as they implement a Kanban system to define and improve their processes. The details of their process, decisions that are made throughout the story, and methods used to communicate and measure their goals, should be treated as examples and not rules. While some groups can make a one-step leap from their current process to using Kanban, this type of instant transformation is risky, especially if the group doesn’t have a realistic and well-defined process.

Late Last Year

Last year the IT Department at ABC Corp became understaffed and started to fall behind on their tasks. Financial pressure convinced the company to delay replacement hiring for several months. Despite the best efforts of the support group, the group started to fall behind on help tickets. Through hard work and overtime the team managed to get the extra work under control and stopped falling behind, but the average amount of time between a request coming in and the task being completed continued to be measured in weeks. Increased numbers of status requests and tasks meant that people were often ‘working’ on ten to fifteen task simultaneously, even basic tasks like connecting new phones or ordering new equipment were being juggled with so many other tasks that the end users felt that the IT Department just didn’t care about their problems.

Current State

It’s now several months later. ABC Corp found some valuable replacements and the overtime has started to come back down. Members of the IT Department are returning to regular schedules and there is a sense of pride in how well they were able to hang on. Unfortunately that sense of pride doesn’t reach outside the walls of IT, where the users have seen a very different picture. The end users still believe the IT Department takes too long to deliver because ’not falling behind’ is different from ‘same day delivery’ and the executive team is questioning whether hiring the replacements was effective or even necessary, as they don’t see improvements in delivery times or performance. Because ABC Corp has a good team, they will probably regain their reputation, the task completion times will come down a bit, the users will start to forget that bad period, and the executives might even see that bringing replacements on board helped the performance of the team. Being students of improvement, though, we can’t allow the team to settle for ’not as late as it could have been’ or ’not as bad as it was’.

Defining Current State

Before attempting to improve the process, we need to know what the process is and determine how it operates. Our initial focus will be to define how the departments process currently works, including the steps they follow while completing work and what the unit of ‘work’ actually is. At this stage we are not trying to figure out how to solve their problems or where the bottlenecks are, we’re simply trying to describe and define the process and tasks. From the beginning, we are going to include members of the team and people in supervisory roles, so that we can be sure we get an accurate picture of the process.

After analyzing processes with the group, we have found that:

ABC Corp accepts customer requests from several different avenues, including email, telephone, walk-ups, and the web-based task system. Once these are received, one of three things happens, either the request is entered into the task system, the person taking the call/email/etc begins executing it right away, or it is recorded in a temporary fashion (sticky note, email client to do list). When a task is completed, there is no defined follow-up process to ensure it met the requestors needs, nor is time taken to enter the task into the system if it had not already been entered.

Visual Board I

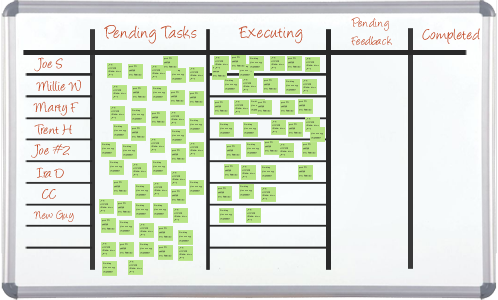

After defining the processes with the team, we have enough information to put together our first visual board. Based on our findings above, we know there are already a number of processes people follow, so we want to make this one as simple as possible to begin with. Our initial goals are to get people to start using this new process and to get people comfortable with it. If we try to make a new process that solves all problems and provides numerous levels of reporting, we will end up with something like the computer system that is already in place and obviously not in consistent use. By starting off simply, we can evolve the board and new process to better fit the team’s needs, rather than trying to create a detail process and then bend the environment to that process.

In the spirit of keeping it simple, we have put together our first Kanban Board by using a whiteboard, some tape, and some sticky notes.

ABC Corp's first visual board – complete with current task sticky notes

Creating a Request

When a team member receives a new request, they are to fill out a sticky note and place it in the ‘Pending Work’ queue. A sample note is posted by the board, along with several stacks of empty notes and writing implements. The sample note has fields for the name of the requestor, the date the task was received, the person that took the request, and a very short description of the request or task. We now have enough information to keep tasks separate on the board, determine how long it took to complete them, find the correct person, if we have questions about the original request, and communicate with the end user about their request. The whole process should take less than a minute and the entry method (sticky note) is simple enough that it can be done while talking to the requestor.

Executing a Request

When a team member starts working on a request they move the corresponding sticky note from the ‘Pending Work’ column to the ‘Working’ Column. Each member of the team has a swimlane on the board to keep the notes organized and so it is obvious who is currently working on a given task. Once the task is completed, it is moved to the ‘Pending Feedback’ column to indicate that the team member is trying to contact the end user to ensure they are satisfied or to walk them through new changes or instructions. Once that has been done, the task is moved to the ‘Completed’ column. When the end user is present for the tasks, such as installing software or setting up a projector, a task may go directly from the ‘Working’ column to the ‘Completed’ column. When a team member completes a task, they enter the completed date on the task note.

Now we spend some time getting our team used to this new process. Each day we check the board in the morning and in the afternoon so we can keep track of how the team is doing and see if anyone needs assistance in using the board (or perhaps less passively going around and reminding people to use the board). At the end of the week, collect the tasks from the ‘Completed’ column and enter the start and end dates in a spreadsheet. By clearing the ‘Completed’ tasks section at a regularly defined interval, we also give the team a visual measurement or goal for the week.

Process Changes and Kanban Limits

After several weeks of using the board, we have brought the team together to review people’s reactions and start working on the next steps. By now the team has gotten used to the process and should be using it consistently. The team has started making the board their first stop when looking for new tasks or answering an end-users question on the status of a request and the starting and completion dates are starting to build a picture of the current delivery times.

Up until now the purpose has been to get the team used to the board and we haven’t put any limits on how tasks are selected, how many someone should be working on at once, etc. This has helped the team engage and helped visualize our current situation, but that visualization is a mess. It’s a good time to start improving the board and introduce improvements to the process.

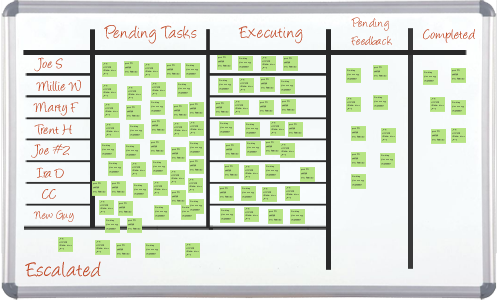

Revising the Process Steps

After talking to the team and reviewing the task notes on our current board, the team has decided to modify the board by adding an area for ‘Escalated Tasks’. This modification was an idea from one of the team members to help us better track tasks that have been escalated to the Systems Administrators and Development groups so they don’t take up space in the ‘Executing’ column – we do not want to lose them by taking them off the board entirely. For the ABC Corp team, this request makes sense, so we add it to the board.

ABC Corp's visual board with new escalation step

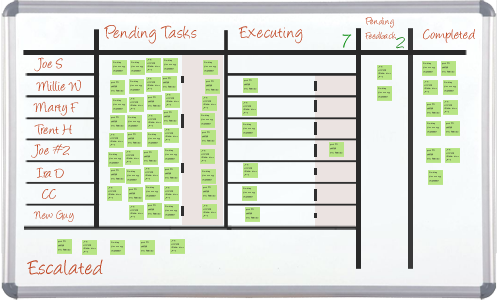

Kanban Limits

One of the important attributes of a Kanban board is the idea of limiting the amount of work in process. In a manufacturing environment, we could use the equipment capacities to help us calculate some viable numbers for each process step, but in our IT Environment we don’t have anything that obvious. We could spend weeks trying to come up with equations or perfect numbers, but instead we are going to just pick some arbitrary numbers based on the number of people we have. If the numbers don’t work perfectly, then we can adjust them a little later and experiment to find a more comfortable set.

We will also assign each member of the group a “home” column. These ‘home’ columns are where people will primarily work. Because the Kanban limits enforce a maximum number of tasks allowed in each process step, there are going to be times when entire sections of the board come to a halt. For instance, if the person responsible for our “Pending Feedback” column gets overloaded or is out sick, the entire department will deadlock because the ‘Pending Feedback’ column is full. When this happens then people will start to move forward from their home column to help clear the bottlenecks.

ABC Corp's visual board with defined limits

Executing Tasks

The last change to our process is going to be how we assign tasks and how they move across the board. Until now, we have not put any restrictions on how or when people select tasks to work on, or how to prioritize new tasks. One of the important concepts of Kanban is to pull tasks or solutions through the process instead of pushing them. At each step our team members will pick up a task from the previous step to work on and they will only do so within the limits placed on their work area or column. To help identify tasks that are ready to be picked up, we have added a shaded area to each column. For the ‘Pending Work’ column, the shaded area holds the next several prioritized tasks, for the rest of the columns it serves as a ‘Completed’ area.

Completed tasks still count against the limits assigned to each column, so if part of the process breaks down, then the task flow will slowly turn into a traffic jam. As team members earlier in the process fill their column, they should move forward to help clear the problem. This ensures that when a complex situation arises, it is dealt with immediately instead of being allowed to sit on the sidelines. This also ensures that even the worst situations are completed in a more timely manner and that delivery times are constantly improved.

Final Analysis

The team has a made a number of gains through this new process, which has also opened the door to continuing improvements and opportunities for good press inside the company.

Process Flow

Initially people worked on numerous tasks at once, splitting attention and losing time as they switched back and forth. With no prioritization there was no guarantee on when a task would be picked up by a team member and tasks could even be misplaced or forgotten altogether. Communications to the end user was inconsistent and escalated tasks were rarely communicated or tracked, while complex solutions were usually not explained and generated additional tasks to complete.

ABC Corp's visual board as time progresses

One member of the team has been assigned to manage end user communications. That team member is responsible for following back up with end users, checking on the status of escalated tasks, answering requests for status updates for pending tasks, and walking users through complex changes or solutions. New tasks are prioritized based on severity level and length of time in the queue and wait in a queue for the next available technician to pick them up. Team members focus on executing a single task at a time and when completed, immediately pass their task on for reporting and select the next highest prioritized task from the pending queue. A distribution is calculated each week of how many days elapsed between task reception and completion and this number serves as a team measurement and source for weekly goals.

The team is gaining on their pending tasks through fewer interruptions, fewer costly attention-switches, and being able to focus a team member on end user communications. End users are receiving more regular communications and time estimates are both firmer and more accurate. Reports to the executives show the number of outstanding tasks shrinking while the total time between reception of tasks and completion has been reduced in variability and duration. T

Achievements

Here are some of the achievements:

- Measurable Results – We have reduced the amount of time between receiving and completing tasks, and for the next several months that duration will continue to shorten until the backlog has been worked through and we find our new pace

- Measurable Improvements – We not only have measured results but we took a baseline before changing the process, which means we now have hard numbers on how far we have improved

- Status at a Glance – The visual board serves as a way to quickly gauge the status of the department, potential problems, and overall work flow or rhythm

- Department Goals – Hard measurements on delivery times serve as a good key indicator of how well the department is performing and provide an excellent measurement for annual goals

- Tighter Estimates – More data and a smoother process has reduced variation in completion times and allows task estimation to be much more accurate

- Morale – Engaging the team members in defining their own process, trying ideas they bring to the table, and allowing them to experiment are all going to raise both morale and respect, which ultimately raises productivity, reduces turnover, and makes the workplace a much more enjoyable place

- Higher Productivity – Work is now being executed more effectively due to reducing the amount of task switching, hunting for information, interruptions for status updates, and lack of prioritization

The advantages above are direct advantages of applying Kanban in a general environment. In the case of ABC Corp, we could probably add several more gains that were more specific to their environment, had they not been a fictional company. Perhaps the biggest gain is that the department now runs from a whiteboard. Someone recently commented that whiteboards, by their nature, invite people to write on them or try and change their content, whereas printed paper has a read-only connotation. How is that relevant? No process is perfect and a process set in stone is a process that is not growing to meet the needs of their company better. By engaging the team members, experimenting, and defining the process on a changeable medium there is encouragement to continue to offer suggestions and to continue and try to improve the process and department.

Next Week

In the next article we will explore using a temporary Kanban process to manage a short-term, functional project. While Kanban is often applied to large processes like a manufacturing line or department process, there are advantages to using it for smaller, throw-away projects as well. In this upcoming story we will look at using a Kanban board to help manage an annual PC replenishment project.

If you have missed prior articles in the series you can find them here:

Applying Kanban … Part 1: Kanban Overview

Applying Kanban … Part 2: Kanban applied to Tech Support

Applying Kanban … Part 3: Kanban applied to PC Deployment

Applying Kanban … Part 4: Kanban applied to a Development Group

Applying Kanban … Part 5: Challenges, Additional Concepts, and Wrapup

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.