This month’s T-SQL Tuesday is being hosted by our very own, Jes Borland (Twitter | Blog). Not only is she hosting this month but she is making it possible for LessThanDot’s first T-SQL Tuesday event. The topic that is brought to us is to discuss with everyone how we solved business problems with aggregate functions. I thought this would be a good time to delete some data so here is my post on the topic.

Duplicates are Evil

Duplicates in data can be detrimental to how you return data from tables. They can be so detrimental that businesses can report large discrepancies on sales, inventory and other critical calculations. Dealing with duplicates begins with the design of you database. It ends with the design of your applications that are inserting data into those databases. Although constraints and everything we can put into maintaining the integrity of our databases are out there for us to use; bad designs happen.

Seek and Destroy

Removing duplicates begins with finding them. Hopefully at the stage in which you are trying to find duplicates in a table (or several), you have proactively found problems they cause before they have had a negative impact on business.

Many methods are out there to find duplicates. Common Table Expressions (CTE) is a known method as well as joining derived tables to each other. In some odd cases, case statements are used along with ranking functions in them. All of these methods are viable solutions but over the years I have come to like the use of COUNT and the HAVING clause. This month’s T-SQL Tuesday on aggregates (e.g. COUNT) got me to thinking this would make a good post.

Some things to consider

COUNT has some concerns. For finding duplicates in a table where a primary key is set as an identity seed, it has challenges. HEAP tables are actually much easier to use this method as the grouping becomes much less complex. One other problem that is well known with COUNT is the fact it does not interpret NULL values.

To show this, let’s create a table named DUPS.

IF EXISTS(SELECT 1 FROM SYS.objects WHERE [name] = 'DUPS')

BEGIN

DROP TABLE DUPS

END

GO

CREATE TABLE DUPS (IDENT BIGINT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, CUST VARCHAR(20), ORDERNUM VARCHAR(20))

GO

CREATE TABLE DUPS (IDENT BIGINT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, CUST VARCHAR(20), ORDERNUM VARCHAR(20))

GO

Now insert some values into this new table with NULL values in the CUST column

INSERT INTO DUPS

VALUES (NULL,'Test'),

('Test','Test'),

(NULL,'Test'),

('Test','Test'),

(NULL,'Test'),

('Test','Test')

You may write a simple query using COUNT to return the count of the column CUST as:

SELECT COUNT(CUST) FROM DUPS

Running this query should return 6. After all, we just inserted 6 rows. It actually returns 3 though.

Looking for duplicates and NULL values plays a key role in what we just went over and using the method I am about to show. Although it is very uncommon that the unique values that are deemed a duplicate would have NULL as an allowable value, bad designs do happen. We are checking for duplicates 😉

Seek

The combination of COUNT, HAVING and GROUP BY is how we will look for duplicates today. We will use a test script that is shown below. The test script creates out table and inserts 10,000 rows. There are three columns. One is the primary key and is an identity insert. The other two are customer number (CUST) and an order number (ORDERNUM). A loop is used to insert test data into the new table.

IF EXISTS(SELECT 1 FROM SYS.objects WHERE [name] = 'DUPS')

BEGIN

DROP TABLE DUPS

END

GO

CREATE TABLE DUPS (IDENT BIGINT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, CUST VARCHAR(20), ORDERNUM VARCHAR(20))

GO

DECLARE @LOOP INT

SET @LOOP = 1

WHILE @LOOP <= 10000

BEGIN

INSERT INTO DUPS

SELECT 'Customer ' + CAST(@LOOP as VARCHAR(5)),

'OrderNum ' + CAST(@LOOP as VARCHAR(5))

SET @LOOP += 1

END

SET @LOOP = 1

WHILE @LOOP <= 10000

BEGIN

IF (@LOOP % 2 > 0)

BEGIN

INSERT INTO DUPS

SELECT 'Customer ' + CAST(@LOOP as VARCHAR(5)),

'OrderNum ' + CAST(@LOOP as VARCHAR(5))

END

SET @LOOP += 1

END

The results from running this transaction will insert 15,000 rows. We know this from using COUNT(*). Ah, COUNT(*) doesn’t care about NULL values. (tip just provided).

The HAVING clause will be exactly what grouping will result from a query. An example of this can be shown by querying the sys.master_files system view for a unique database ID.

SELECT

SUM(database_id)

FROM sys.master_files

GROUP BY database_id

HAVING database_id = 1

To use this in a duplicate search, add COUNT to the HAVING clause

SELECT

database_id

FROM sys.master_files

GROUP BY database_id

HAVING COUNT(database_id) > 2

This would show us the entire database ID’s that have more than 2 files associated with them.

Taking this to work for us with our earlier table and data, we could do the following

SELECT

MAX(IDENT),

ORDERNUM

FROM DUPS

GROUP BY ORDERNUM

HAVING COUNT(ORDERNUM) > 1

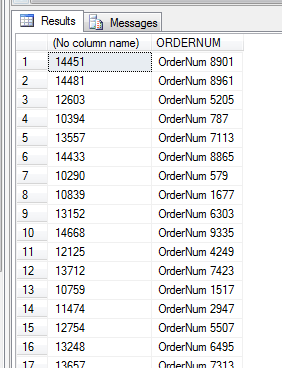

The results shown list all the order numbers that are found to be duplicates (or more than 1)

Destroy

Loaded with this information, adding a DELETE to the statement and anything that is not listed as our MAX identity, will remove all duplicates and leave the last one inserted (based on the identity seed)

DELETE FROM DUPS

WHERE IDENT NOT IN (

SELECT

MAX(IDENT)

FROM DUPS

GROUP BY ORDERNUM

HAVING COUNT(ORDERNUM) > 1)

Once this statement is executed, the table is cleansed of the duplicates and back to the row count of 10,000 unique order numbers.

Note: Always back you table up before you delete large amounts of data. This can be done (if the data is not too large of a volume) with a DBA designated database set in simple recovery and using SELECT INTO. Always ensure you have a quick recovery plan.

The MIN can also be used if the first inserted row is to be retained. The other CTE method mentioned earlier can also be done by using PARTITION BY and ROW_NUMBER

;WITH DUP_CTE AS

(

SELECT ORDERNUM,ROW_NUMBER() OVER (PARTITION BY ORDERNUM ORDER BY (SELECT 0)) RN FROM DUPS

)

DELETE FROM DUP_CTE

WHERE RN <> 1

This allows more selectivity to the row ranking and removal process.

There you have it. Delete away! (kidding, make sure you delete what you are supposed to be deleting)