There are several considerations when deciding if your Merge Replication setup is in need of an article that uses Row-Level Tracking or Column-Level Tracking. The primary considerations will be the business needs and overall data retention needs. Can you allow subscriber data to be lost if it is not the last updated data? At the highest level, Row-Level Tracking is performed based on a datetime column and determining if the row has a conflict, and using the date column to determine resolution based on a resolver. Column-Level will allow conflict resolution based on a date column using a resolver, as well as a merge aspect of the column level changes by both Publisher and Subscriber. Aside from the business, from a DBA’s perspective, performance will be a factor in deciding which setting to use on an article. Although the base decision will always be determined by what the business application dictates, performance considerations may direct development to other integration aspects that are considered acceptable data merging practices for the given business rules.

Tracking Differences

Although Column-Level tracking may seem like it would take more resources to implement, there is less overhead in terms of what is transferred between Publisher and Subscriber. Column-Level Tracking does implement a great deal more in terms of Merge Replication tracking and system table storage causing higher resource consumption on synchronizing. Careful tuning of the merge system tables with Column-Level tracking can be done to assist in a higher overall performance during synchronizing. With Row-Level tracking, there is no choice in Merge Replication processing but to send the entire row that was updated.

Take the Sales publication that was setup in the article, “Merge Replication – Filtered Data Publication Setup” and the SalesOrderHeader article. SalesOrderHeader utilizes Column-Level Tracking and a resolver of Later Wins on OrderDate. This means, if a change is made to the Publisher on the column DueDate and a change was made on the Subscriber to column BillToAddressID, the DueDate change from the Publisher and the BillToAddressID change from the Subscriber would be merged, resulting in a row with both updated columns. Now, if a Publisher change on DueDate was made and a Subscriber change on DueDate was made on the Subscriber, the most recently updated column would be the winning result. The same change to DueDate on both Publisher and Subscriber would result in a conflict also. This conflict could be handled in a custom resolver that implements business logic and a decision could be made to merge, or retain in some way, both values. With these examples, the data volume transferred between the Publisher and Subscriber would be less, but there would be a great deal more intervention by Merge Replication to determine all of this in order to make the right decision based on the settings for the article.

Let’s look at the merging of data with Column-Level Tracking and what is transferred based on the lineage of the row and column. Merge Replication will utilize the lineage columns in MSMerge_Contents to determine if there are differences in versions. This is done by comparing the lineage values, which are binary data types. When Column-Level Tracking is enabled, the colv1 column, which is the lineage of the columns of a row, is populated in MSMerge_Contents. If Row-Level Tracking is enabled, colv1 will be 0x00.

(Refer to “Merge Replication – Filtered Data Publication Setup” to setup the Publication and Subscription that is used)

We will focus on SalesOrderHeader.SalesOrderID 75123. Ensure that updates have been made to the SalesOrderID prior to this example and you have synchronized the updates. If no changes or subscriber traffic has occurred on the publication database, the MSMerge* tracking tables will be empty at that time. To show how the level tracking functions, it is best to update a subscriber and merge the changes before this running these examples. You can use the same update statement below to perform that initial update and merge event._

update Sales.SalesOrderHeader

set ShipDate = getdate(), OrderDate = getdate()-10,DueDate = getdate()-1

where SalesOrderID = 75123

set ShipDate = getdate(), OrderDate = getdate()-10,DueDate = getdate()-1

where SalesOrderID = 75123

Before replicating to the publication database, check the MSMerge_Contents and MSMerge_Genhistory to see the pending changes on the subscriber that we just performed.

SELECT

contents.generation,

contents.lineage,

contents.colv1,

gen.coldate,

gen.art_nick,

gen.changecount

FROM MSmerge_contents contents

join MSmerge_genhistory gen on contents.generation = gen.generation

join Sales.SalesOrderHeader upd on contents.rowguid = upd.rowguid

where SalesOrderID = 75123

and genstatus = 0

The query above shows that the update performed earlier is in a pending state on the subscriber. This is determined by utilizing the genstatus column in MSMerge_Genhistory. The genstatus values can be “0 = Open”,“1 = Closed” or “2 = Closed and the update was taken from another subscriber”. This information can be critical to tracking where updates originated from while troubleshooting.

Now that we have seen how to find the pending changes on the subscriber and return the row and column lineage values, use the lineage values to determine the subscriber that made the changes, actual versions and columns that were changed. To do this, use the statement below.

declare @lineage varbinary(311)

declare @colv varbinary(311)

SELECT @lineage = lineage, @colv = colv1 FROM MSmerge_contents contents

join MSmerge_genhistory gen on contents.generation = gen.generation

join Sales.SalesOrderHeader upd on contents.rowguid = upd.rowguid

where SalesOrderID = 75123

and genstatus = 0

exec sp_showlineage @lineage

exec sp_showcolv @colv

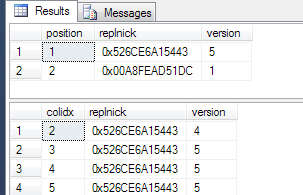

The position column represents the actual column position for the results from running sp_showcolv. This coincides with the actual cardinality of the columns in the table. In our results, columns 3, 4 and 5 are showing a version number of 5. Checking INFORMATION_SCHEMA.TABLES we can return the position and then match it up to the position returned from the sp_showcolv procedure.

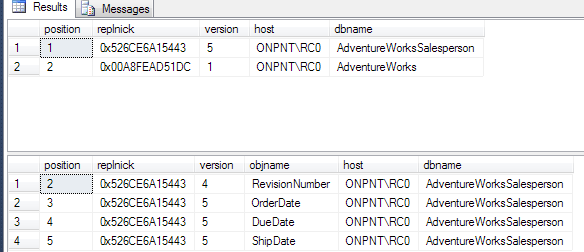

The following script shows how we can match these values all together in order to return meaningful information regarding the actual lineage and where updates originated.

declare @lineage varbinary(311)

declare @colv varbinary(311)

declare @articlename nvarchar(128) = 'SalesOrderHeader'

create table #colv_results (position smallint, replnick binary(6), version int)

create table #row_results (position smallint, replnick binary(6), version int)

SELECT @lineage = lineage, @colv = colv1 FROM MSmerge_contents contents

join MSmerge_genhistory gen on contents.generation = gen.generation

join Sales.SalesOrderHeader upd on contents.rowguid = upd.rowguid

where SalesOrderID = 75123

and genstatus = 0

insert into #row_results

exec sp_showlineage @lineage

insert into #colv_results

exec sp_showcolv @colv

alter table #row_results add host sysname, dbname sysname

alter table #colv_results add objname sysname, host sysname, dbname sysname

update a

set host = subs.subscriber_server,

dbname = subs.db_name

from #row_results a

join sysmergesubscriptions subs on a.replnick = subs.replnickname

update a

set host = subs.subscriber_server,

objname = COLUMN_NAME,

dbname = subs.db_name

from #colv_results a

join sysmergesubscriptions subs on a.replnick = subs.replnickname

join INFORMATION_SCHEMA.COLUMNS cols on a.position = cols.ORDINAL_POSITION

and cols.TABLE_NAME = @articlename

select * from #row_results

select * from #colv_results

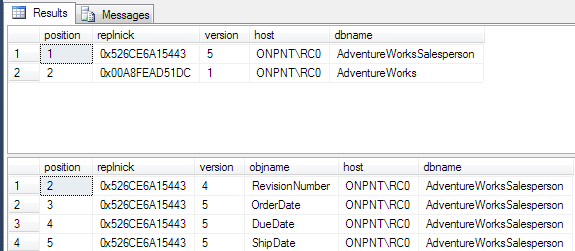

Run the same script on the publication database so the versions can be compared. Comment out the line and genstatus = 0 as the genstatus of the rowguid will be in the state of the last closed generation.

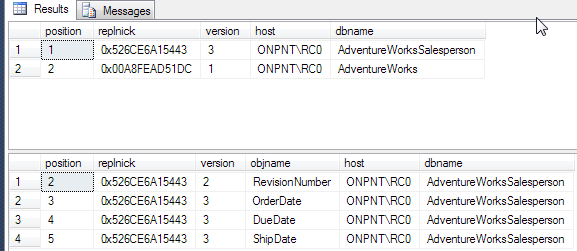

As shown above, the versions on the publication database for the columns and specific rowguid are lower than the versions shown on the subscriber.

This has shown that the columns that were updated are the only ones transferred in the colv1 column. That may seem to be a situation where performance would be better but this also shows the added processing that is required during the actual synchronization process.

Run the merge agent so the subscriber is synchronized with the publication. Once completed, run the script from earlier to show the versions for each column. We’ll see that they have all been updated and now the versions match between the publication and the subscriber.

Results from the publication database

Performance

To show the difference in performance, a mass update has been executed on the SalesOrderHeader on the publication database. The update changes the SalesPersonID and LoginAccount so the rows will be included in the partitioned snapshot.

update Sales.SalesOrderHeader set SalesPersonID = 275, LoginAccount = 'ONPNTtkrueger'

where SalesOrderID IN (SELECT TOP 10000 SalesOrderID from Sales.SalesOrderHeader

Order by OrderDate desc)

Once the update statement has been executed, the subscription was removed and a snapshot was run on the publication. When the snapshot was completed, the subscription was added back and the snapshot applied.

Next, the subscriber database was updated for all the SalesPersonID of 275. This results in 10388 rows being updated.

update Sales.SalesOrderHeader

set ShipDate = getdate(), OrderDate = getdate()-10,DueDate = getdate()-1

where SalesPersonID = 275

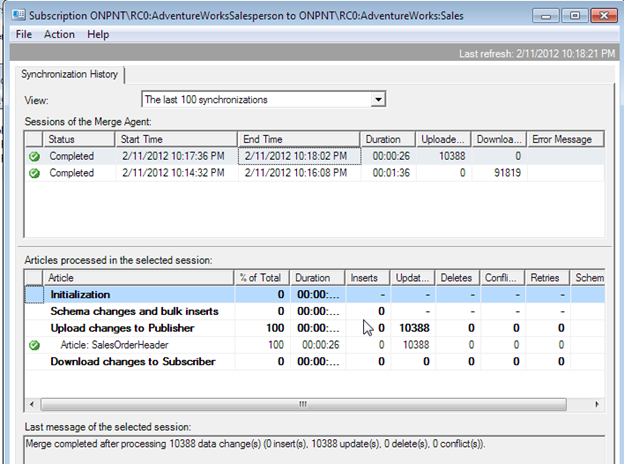

Results from applying the snapshot and synchronizing

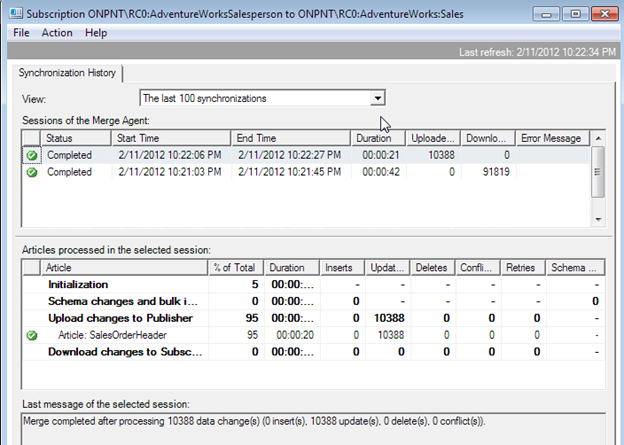

Now, alter publication and article SalesOrderHeader to use Row_Level Tracking. Create a new snapshot and re-initialize the subscriber. Run the same update statement to SalesPersonID of 275 as performed on the Column-Level Tracking enabled article.

Results with Row-Level Tracking

This shows quite a difference in both the snapshot applying and the synchronization steps.

Column-Level Tracking

Snapshot = 1.36 Minutes

Synchronization = 26 Seconds

Row-Level Tracking

Snapshot = 42 Second

Synchronization = 21 Seconds

Although the replication monitor results for total duration do not go to a milliseconds level, it shows the differences in the two types of tracking that are done for duration in both synchronizing and applying snapshots. The replication monitor is also commonly used to show performance and is a great comparison in testing. In our test, Column-Level Tracking having a longer overall duration is directly tied to the added need for Merge Replication to maintain and process more metadata while Row-Level Tracking is a shorter overall process and needs less metadata work.

Which to use?

This example has shown that there is a cost between using Row-Level and Column Level tracking on articles. The business and application needs will always come first though. The need for Column-level Tracking may be unavoidable but with this knowledge, going into a publication design with articles enabling Column-Level Tracking can be valued in being proactive on adding performance tuning prior to implementing your publications into a production environment.