This is a follow-up article to, “Index Seek on LOB Columns". While working on the demonstration for the computed column method to achieve index seeks on a LOB data type, I noticed the lob logical reads were exactly twice the row count in the table that the queries were being executed on. For example, the exact row count of PerfLOB was 100. When running the query shown in listing 1, the statistics IO show exactly 200 lob logical reads.

SELECT LEN(LOBVAL), SUB_CONTENT FROM PerfLOB WITH (INDEX=IDX_LOGSTRING)

Note: To follow the examples in this article, please refer to the scripts in Index Seek on LOB Columns and utilize the Word document available for download, “Columnstore Index Basics”.

I recalled reading an article by Paul White, “Beware Sneaky Reads with Unique Indexes” that explains the reasoning to why these reads were coming in higher. As always, Paul’s deep understanding of and ability to explain the optimizer’s internals are shown in the article.

To understand the query in listing 1 and the read counts, let’s investigate the pages.

First, create a new table and insert 100 Word documents into it. Change the path to a Word document on your system that the SQL Server service account has access to.

CREATE TABLE PerfLOB (ID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, LOBVAL VARCHAR(MAX), SUB_CONTENT AS (CONVERT([varchar](100),substring([LOBVAL],(1),(100)),0)))

GO

INSERT INTO PerfLOB (LOBVAL)

VALUES ((SELECT * FROM OPENROWSET(BULK N'C:NoSecColumStoreIndexBasics.docx', SINGLE_BLOB) AS guts))

GO 100

Next, create the index that utilizes the computed column and the nonkey LOBVAL column.

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX IDX_LOGSTRING ON PerfLOB (SUB_CONTENT) INCLUDE (LOBVAL)

Set statistics IO on and run the query below:

SET STATISTICS IO ON

SELECT LEN(LOBVAL), SUB_CONTENT FROM PerfLOB WITH (INDEX=IDX_LOGSTRING)

The IO from this query should show these results:

(100 row(s) affected)

Table ‘PerfLOB’. Scan count 1, logical reads 4, physical reads 0, read-ahead reads 0, lob logical reads 200, lob physical reads 0, lob read-ahead reads 0. (1 row(s) affected)

SQL Server 2005+ Investigation

Immediately we can see, even knowing we inserted only 100 rows into the table, we return 200 lob logical reads. The reasoning for this is due to the need to read in the LOB pages. Using DBCC IND and DBCC PAGE commands, we can look into the internals of the pages and how they are being pulled to satisfy the query and, more importantly, why the reads are exactly twice the number of the row count in the table.

Create a table to hold the DBCC IND results so they can be reviewed easier.

IF EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM sys.objects WHERE object_id = OBJECT_ID(N'[dbo].[IND_Results]') AND type in (N'U'))

DROP TABLE [dbo].[IND_Results]

GO

CREATE TABLE IND_Results

(

PageFID tinyint,

PagePID int,

IAMFID tinyint,

IAMPID int,

ObjectID int,

IndexID tinyint,

PartitionNumber tinyint,

PartitionID bigint,

iam_chain_type varchar(30),

PageType tinyint,

IndexLevel tinyint,

NextPageFID tinyint,

NextPagePID int,

PrevPageFID tinyint,

PrevPagePID int

);

GO

Using DBCC IND and Dynamic SQL with the EXEC command is a common method to insert the results into a static table for later review. It is a reliablemethod for capturing results as well.

To insert the DBCC IND results, use Exec as shown below

INSERT INTO IND_Results EXEC ('DBCC IND (QTuner, ''dbo.PerfLOB'', 2)')

GO

The above DBCC IND command will return the information on the index ID 2; index IDX_LOGSTRING. For more information on DBCC IND, read Paul Randal’s article, “Inside the Storage Engine: Using DBCC PAGE and DBCC IND to find out if the page splits ever roll back”

To read further on DBCC IND and the page types that can be returned in the results, read “Inside the Storage Engine: The Anatomy of a page”, by Paul Randal.

Before looking too deep into the DBCC IND results, do a direct select on the IND_Results table to return all the information returned.

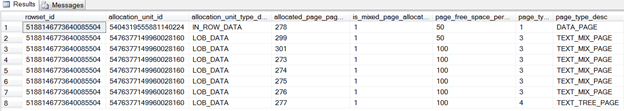

SELECT * FROM IND_Results

In the results above, we see that the data pages, PageType = 2, are shown first. These pages contain the SUB_CONTENT column of the nonclustered index. Once page 20388 appears, the LOB pages come in. Immediately there is a noticeable difference in the PageType values. PageType contains both 3 and 4. Here is where we answer the question of why we return exactly twice as many reads as rows in the table.

Both page types 3 and 4 are LOB data pages or more appropriately-named text pages. Page type 4 contains a text tree and a large amount of the LOB data. Page type 3 contains more LOB data relating back to the tree. So in the results above, page 20411 starts the chunk of LOB data and relates back to a series of page types of 3.

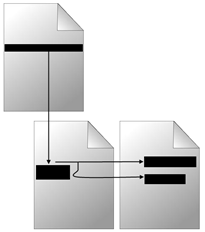

To visualize this, imagine the page layout shown below starting with the root page.

Note: the ordering of the pages as they are stored does not always go in order depicted. Page 20411 starts and contains the text tree to pages 20413 to 20417. Also, page 20411 may not relate directly to the other pages but the illustration shows a good visualization to the effects of the text page type relations and tree sharing.

This still doesn’t answer the amount of reads until we look at the pages that are PageType 4.

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM IND_Results WHERE pagetype = 4

The above query to count all page types of 4, results in 100. In this case, the nonclustered index key column is, in a way, chained back to the 100 pages of type 4. In order to retrieve the pages needed, the key column is read as well as the LOB data pages of page type 4. So this shows the 200 reads that take place while the task to read in all the pages, including the LOB pages, is performed.

It is important to mention that the document that was tested and the needs it had in terms of how much storage, is the reason for the number of text tree pages needed. Given a document that was smaller or larger, the text tree pages may have been smaller or larger.

SQL Server 2012

To further investigate how the storage is handled, and to look at the page types, take a more static and direct approach as shown below. Performing this method allows us to remove the possibility of variable results based on a LOB insert from a document that may cause different page count needs.

USE tempdb;

SET NOCOUNT ON;

IF OBJECT_ID(N'Test', N'U') IS NOT NULL DROP TABLE dbo.Test;

CREATE TABLE dbo.Test (lob varchar(max) NOT NULL);

GO

INSERT dbo.Test VALUES (REPLICATE(CONVERT(varchar(max), 'X'), 40 * 1024));

GO

(Code example written by Paul White (B | T) – Thanks again, Paul!)

The code example above creates a testing table, “Test” and inserts enough data into the variable max column to exceed the 32KB size. Once LOB data exceeds 32KB in size, this causes the page to require the pointers discussed earlier. A text pointer from the data row is created and then follows through to the text root (page type 4) structure. As stated, the text tree then points down through to the LOB data stored on one or more text pages (page type 3).

With SQL Server 2012 a new undocumented DMV can be used to look further into the page storage and types, sys.dm_db_database_page_allocations.

SELECT

rowset_id,

allocation_unit_id,

allocation_unit_type_desc,

allocated_page_page_id,

is_mixed_page_allocation,

page_free_space_percent,

page_type,

page_type_desc

FROM sys.dm_db_database_page_allocations(DB_ID(N'tempdb'), OBJECT_ID(N'Test', N'U'), 0, 1, 'DETAILED') AS dddpa

WHERE

dddpa.is_iam_page = 0;

From the results, the illustration below shows a more descriptive layout of the pages. This is seen more clearly in the page_type_desc results.

Summary

The true advantage to knowing how data and specific data types are stored allows us to better manage storage and performance. This is done by constructing unique disk structures for LOB, database structures and other tuning methods. Reviewing how a query is affecting disk and overall IO can be extremely beneficial while working to lower the overall need for excessive IO.

LOB data in particular has a unique storage structure. While working with LOB data, take into account what we’ve gone over and how you can better enhance the overall experience.