Recently I presented at SQLSat 83 about VLF’s and their performance impact on our databases. I decided to write this post as well for everyone who couldn’t make it all the way to Johannesburg, South Africa.

To provide a bit of history on the subject, I was tasked in March to evaluate a server which came under severe strain. After investigating the numerous issues from insufficient memory to slow internal disk space ( raised alerts in SQL log, and monitoring some of the buffer and memory counters in perfmon), I came to the intermediate solution to redo the log allocation.

T-Log Overview:

Before we dive into the virtual log files, let’s take a quick recap on what the T-Log is and how it works.

What is a Transaction Log and How Does it Work?

A transaction log is a record of all modifications made to a database, including system stored proc’s, DDL statements, begin/end of a transaction, extent allocation/deallocations, etc. It is also the key roleplayer in restoring back ups, point-in-time recovery(FULL recovery model only) and transactional and merge replication. A log record for each modification is made in the log cache, and a LSN(log sequence number) is assigned to the modification.

SQL Server uses a read-ahead log model; this means that any data modifications are not immediately made to the data directly, rather a copy of the data residing in memory. Let’s see how it works:

- SQL will first check the buffer cache if the required data page is there.

- If the data page is not found, then it will make a copy to the buffer cache.

- The data modification is applied to data page in the buffer cache.

- When the data page is written to disk, it is called a page flush.

- The log will write all of the modified data pages to disk via the lazy writer when;

- A CHECKPOINT occurs.

- A COMMIT TRAN occurs.

- Transactional/Merge replicated transactions are transfered to the subscriber.

- Space is required for new data pages.

- Note, when a modification is written directly to disk without a log record being created; that modification cannot be rolled back until the next FULL backup is made.

The use of the read-ahead log model ensures that the ACID principals are not broken and to ensure redundancy, integrity as well as a recoverable database when you are using FULL recovery model.

Virtual Log Files:

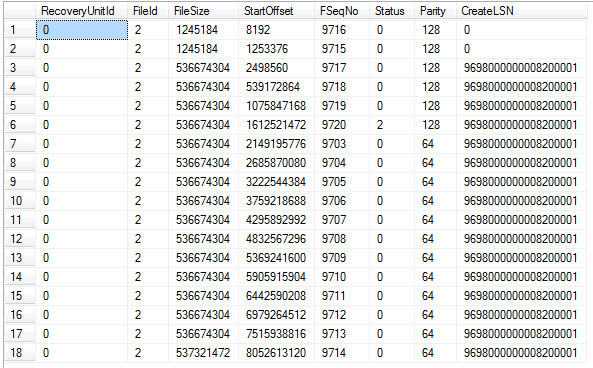

VLF’s is what makes up the transaction log internally. We can see the VLF’s with the following command:

DBCC LOGINFO(DB_Name)

You should then see something similiar to this:

Columns of note are:

FileSize – file size in bytes.

Status – 0 not in use, 2 in use.

CreateLSN – Log Sequence Number.

When looking to optimize the T-Log we are looking actually looking to allocate the right number, and correctly sized VLF’s. When VLF’s are created, either by autogrow or a manual grow; a certain number of VLF’s are allocated according to the size.

< 64MB will create 4 VLF’s

= 64MB < 1GB will create 8 VLF’s

and > than 1GB will create 16 VLF’s.

This is by design due to the algorithms used within the SQL Engine. If you create a new database, and pre create the log file with 16GB, then you will have 16 VLF’s with a size of 1GB each.

In some cases you do not want to pre create the log file with a size that might make your VLF’s unmanageable like a 64GB log. A 64GB log will create 16 VLF’s with a size of 4GB. This can be problematic because a VLF is only cleared after it has been filled, but the same account to having VLF’s which is too small.

“Why don’t you create multiple log files to ensure that transactions are split?” is a popular question, with a simple answer. The T-Log works sequentially and in a round robin fashion. The only benefit in adding multiple log files is redundancy, in case the drive or RAID configuration fails for the particular log file.

The Test

I created a 50,000 row data set, for two databases using Data Generator from Red-Gate Software.

Below is the schema for the table:

CREATE TABLE [dbo].[vlftab]( [ID] [int] IDENTITY(1,1) NOT NULL, [comment] [varchar](8000) NOT NULL, [Name] [varchar](20) NOT NULL, [surname] [varchar](40) NOT NULL, [DoB] [date] NOT NULL, [acc] [int] NOT NULL, [joindate] [datetime] NOT NULL)

I then used three basic statements to test how long it takes to complete:

update presentation_fast..vlftab set comment = upper(comment),

name = upper (name),

surname = upper(surname)

insert into Presentation_fast..vlftab select comment, Name, surname, DoB, acc, joindate from Presentation_Fast..vlftab_source;

delete from Presentation_slow..vlftab

Following company policy, I created for the SlowDB a log file which is 30% of the data size. This resulted in a log file which is 75MB. I manually grew the log in increments of 15MB, this resulted in 20 VLF’s each with a size of 3.75MB. The second database, using the exact same data had a 8GB log with 16VLF’s each sized 512MB.

The results of the queries are as follows:

| Insert(ms) |

| Update(ms) |

| Delete(ms) |

It’s quite shocking to see how something like this can affect a database, and the impact it can have on business. IF the log is allocated correctly, then it shouldn’t auto grow which in some cases can cause that incorrectly sized VLF’s are created, which could hamper performance.

Conclusion

Optimizing the transaction log escapes most of us when it goes further than the best RAID configs, or SSD’s. But on systems without these configurations this can often be the solution to poor performing databases when every other avenue have been explored.

For systems, to properly allocate the log file; is testing. A good tool I found for this is SQLStress as it can simulate different workloads and it’s flexible.