Model-View-Presenter is an architecture pattern that defines a structure for behavior and logic at the UI level. M-V-P separates the logic of the presentation, such as interacting with back-end services and the business layer, from the mechanics of displaying buttons and interface components.

I often build small projects to help understand and grow my skills as a developer, architect, and all-around technologist (as may be apparent from the wide range of topics I post on). Today I worked with a combination of Visio and Visual Studio to build a sample project to play with the Passive View concept and to help grow my own understanding of the concept. This post will cover the Visio side of my learning-curve.

You can read more about Model View Presenter at Wikipedia and <a href=http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/cc188690.aspx"" target="_blank" title=“Model View Presenter by Jean-Paul Boodhoo on MSDN”>MSDN. Perhaps the best information can be found on Martin Fowler’s site, where he has separate write-ups on <a href=“http://www.martinfowler.com/eaaDev/PassiveScreen.html" target=_blank” title=“Passive View pattern”>Passive View and <a href=“http://www.martinfowler.com/eaaDev/SupervisingPresenter.html" target=_blank” title=“Supervising Controller Pattern”>Supervising Controller.

Passive View

Passive View is a subset of the Model-View-Presenter pattern. In Passive View, the interface is responsible for handling interface-specific logic, such as figuring out how to put a value in a textbox or react to events from button clicks, but all actions and logic outside of the raw UI are sent to the Presenter to execute or manage. The Presenter is responsible for calling business methods in the Business model and updating the data that is available in the View.

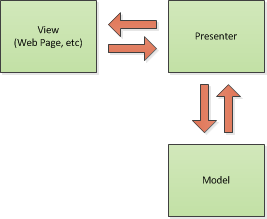

Basic Model-View-Presenter Diagram

From the outside in, the architecture for Passive View looks something like this:

- UI – The User Interface reflects what is going on beneath it by implementing one or more View interfaces

- Presenter – The Presenter receives interactions from the UI or Model and updates the Views it is attached to

- Model – The model is a facade or black box in our diagram, behind which is a business logic layer and data layer

In a flat architecture we would collect data from the interface, perhaps do some business and data validation, and then save it directly to a database using stored procedures or inline SQL. Defining a data access layer (or data model like entity framework) allows our application to operate on cohesive, defined objects that are meaningful to the application and stored and retrieved consistently. Defining a business logic layer allows us to centralize business rules that operate on entities in our application in a manner that is consistent with the business and internally consistent in the application, minimizing the risk that occurs when making changes to the business flow. Separating the logic of populating inputs and responding to button presses on the UI from the information being communicated to the end user and conceptual responses to their input allows the system to interact with the user consistently across any number of interfaces into the same application.

The definition of each level increases our ability to automate testing and supports greater Separation of Concerns.

Implementing a Sample Project

My learning exercise has been the the creation of an ASP.Net search page that allows an end user (customer) to search for finished products from the AdventureWorks sample database. The architecture and design decisions were done as an exercise in Visio using simple shapes and layouts.

My example application has several functional and non-functional requirements:

- Functional – Display product number, name, list price, and available quantity in tabular format

- Functional – Provide a basic search input and button to search product names

- Non-Functional – Implement an M-V-P pattern – Obviously the purpose of this whole exercise

- Non-Functional – Use a simple model stack that can be easily replaced with a Service-Oriented one at a later time

- Non-Functional – Build with the idea that we will later create a Silverlight or WPF front-end

- Non-Functional – Make pretty pictures for article

My unwritten, final requirement was to finish the whole thing in half a day, though luckily I didn’t define whether I intended that to mean 4 hours or 12.

Initial Architecture

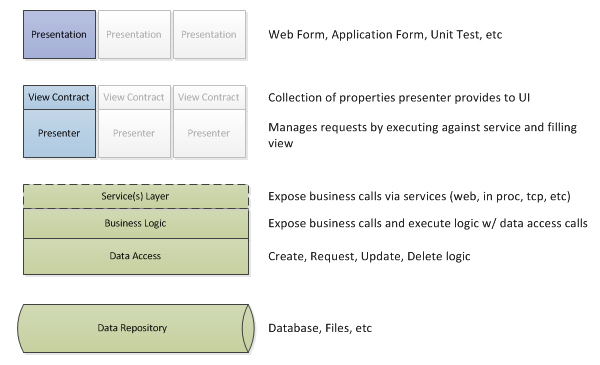

To start I created a diagram of the application architecture:

More Extensive Model-View-Presenter Diagram

The purple layer is my presentation layer, which reflects the View. The blue layer is my Presenter layer which contains the logic for interacting between the end user and interface as well as a definition, or contract, of the information available in the View. The Green is the Model (or is behind the model, depending on your viewpoint) and exposes business functions and data entities for the Presenter to interact with.

Class Layout

Once the high level diagram was completed, I could approach the task of creating some base classes and interfaces to use in implementing the project.

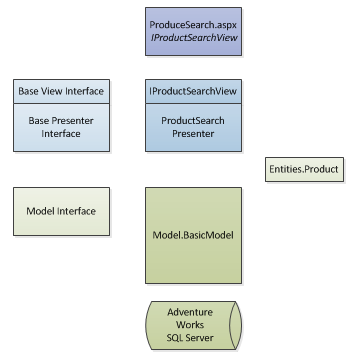

- Model.IModel – Generic Model Interface to expose business calls to Presenters

- Presenter.IView – Generic View Interface that all Presenters can interact with and all screens implement

- Presenter.BasePresenter – Generic Presenter class that all Presenters will implement

To keep the project to a single morning but also allow the ability to come back and build a more architecturally sound solution, I implemented the Model in a very basic fashion that was referenced locally by the Presenter project and makes direct calls to SQL Server using ADO and parametrized, inline SQL. This buys me the benefits of having a well-defined Model (via the interface) but allows me concentrate my time and effort on the learning part of the project (ie, the M-V-P interaction and structure). Defining the model interface also leaves me open to come back and replace it with better separated code and the ability to create a model that acts as a facade to a service stack, instead of local DLLs.

- Model.BasicModel.Model – Basic implementation of a model that will interact with AdventureWorks on SQL Server

- Model.Entities.Product – A Product Entity that can be communicated between an IModel instance and Presenter

- Presenter.ProductSearchPresenter – A Presenter to manage product search interface

- Presenter.IProductSearchView – A view of the data involved in a product search

- ProductSearch.aspx – A web page that implements the IProductSearchView and interacts with the ProductSearchPresenter

My final Visio diagram ended up looking like this:

Diagram of Example Application

In this case the left side represents basic components (bases classes and interfaces) that are used to define common structure or contracts on the right side.

The Code

For the purposes of the example project, my view has properties for Search Text, a Search Count (number of results), Results (a generic list of the Product entity), and a boolean indicating whether there are results to display. My Web Form implements these properties, tying them to elements on the screen.

public partial class WebForm1 : System.Web.UI.Page, Presenter.Views.IProductSearchView {

Presenter.ProductSearchPresenter _presenter;

protected void Page_Load(object sender, EventArgs e) {

btnSearch.Click += new EventHandler(btnSearch_Click);

rptProducts.ItemDataBound += new RepeaterItemEventHandler(rptProducts_ItemDataBound);

_presenter = new Presenter.ProductSearchPresenter(new Model.LocalModel.BasicModel(System.Configuration.ConfigurationManager.ConnectionStrings["AdventureWorks"].ConnectionString), this);

}

void btnSearch_Click(object sender, EventArgs e) {

this._presenter.ExecuteProductSearch();

}

string Presenter.Views.IProductSearchView.SearchText {

get { return tbSearch.Text; }

set { tbSearch.Text = value; }

}

int Presenter.Views.IProductSearchView.ResultCount {

set { lblResultCount.Text = value.ToString(); }

}

List<Model.Entities.Product> Presenter.Views.IProductSearchView.SearchResults {

set {

if (value != null && value.Count > 0) {

rptProducts.DataSource = value;

rptProducts.DataBind();

}

}

}

bool Presenter.Views.IProductSearchView.DisplayResults {

set { tblResults.Visible = value; }

}

...

As the presenter populates properties in the view, the information is automatically reflected on the page. The actual logic of how the business functions are called and populate those properties are neatly packaged up in the Presenter and View interface and very little logic occurs in the actual web form.

public class ProductSearchPresenter : BasePresenter {

protected Views.IProductSearchView _view;

public ProductSearchPresenter(Model.IModel model, Views.IProductSearchView view) : base(model) {

this._view = view;

this._view.ResultCount = 0;

this._view.DisplayResults = false;

}

public void ExecuteProductSearch() {

List<Model.Entities.Product> results;

results = this._model.SearchProduct(this._view.SearchText);

if (results.Count > 0) {

this._view.ResultCount = results.Count;

this._view.DisplayResults = true;

this._view.SearchResults = results;

}

else {

this._view.ResultCount = 0;

this._view.DisplayResults = false;

this._view.SearchResults = null;

}

}

}

To create a unit test, we define a simple view that implements the view interface, execute the presenter logic, and verify the properties are populated the way we would expect when the same presenter calls are made from the interface.

Extending the Architecture Further

Extending the application to display product search in a different manner would only require the addition of a new interface that also implements the Product Search View. A Silverlight front-end would only require creating the basic project, implementing the product search View, and wiring the new interface controls to the view properties. To replace the direct mode reference with a service reference, we could create a service facade that implemented the IModel interface, connected to a local or remote WCF service behid the scenes to handle the real model logic. And finally, instead of counting on our QA department to test all of the application interactions, we can create unit tests directly against the Presenter and Views to ensure that all of the interactions below the top surface of the application are happening consistently and to our expectation.

Your Turn

Getting this much of the architecture working is a good first step. I took a number of shortcuts on the BasicModel class in my example, but I now have a functional Model-View-Presenter application to play with. Hopefully there was enough information in the article to interest you in trying this out on your own. I urge you to read the articles linked in the top of the post (or several more in my Model-View-Presentation bookmarks) and come up with your own diagrams and sample project. Even doing a small project will force you to run into questions and considerations you wouldn’t have had by simply reading about it, not to mention unrelated tidbits you will pick up along the way (for instance, I also learned about ObservableCollections today).

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.