In SQL Server 2005 to 2012, row limits took on a slightly new limit expectation when variable length data types were used: varchar, nvarchar, varbinary, sql_variant or CLR. Essentially, this is done by the addition of a large object page: Row Overflow Pages or pages in the ROW_OVERFLOW_DATA allocation unit. The row overflow page type allows a row to exceed the 8060 byte row limitation by performing exactly what the name implies by extending the row into an overflow page. In order to accomplish this, a 24 byte pointer is retained on the original pages which still reside in the IN_ROW_DATA allocation unit. This is also the same when multiple row overflow pages are introduced. The row overflow pages can be another factor when indexing and reviewing existing execution plans. The end result should be to generate a good execution plan while bringing in as few pages as needed to fulfill the needs of the transaction.

CREATE TABLE SpanOverFlow (COL1 VARCHAR(8000),COL2 VARCHAR(8000),COL3 VARCHAR(8000),COL4 VARCHAR(8000),COL5 VARCHAR(8000),COL6 VARCHAR(8000),COL7 VARCHAR(8000))

GO

Listing 1

In listing 2, the insert statement greatly exceeds the 8060 byte row limit by 39,940 bytes. This would introduce 1 IAM page in row overflow page and 7 row overflow page listings. It may be thought that this would create 6 page type of 3 (Row Overflow Page Type) due to 6 pages being enough to hold the 6 variable length columns that now hold 8000 bytes per column. However, when a row overflow page is introduced, the column with the largest width is moved out of the in row allocation unit and into the overflow allocation unit. In this case, the largest column is moved first, creating the first row overflow page and then the next 6 are moved as well. Since one page can withstand the same 8060 byte row size and the originating page is now free (taking into account the pointers), this equates to 7 row overflow pages.

INSERT INTO SpanOverFlow SELECT REPLICATE('0',8000),REPLICATE('0',8000),REPLICATE('0',8000),REPLICATE('0',8000),REPLICATE('0',8000),REPLICATE('0',8000),REPLICATE('0',8000)

GO

Listing 2

To review the current pages for a table, including the row overflow pages, the undocumented DBCC IND command can be used as shown in listing 3.

DBCC IND('QTuner','SpanOverFlow',1)

Listing 3

Another, more simplistic method using the DMV (Dynamic Management View) sys.dm_db_index_physical_stats, can be used but is limited to showing the allocation units that exist for the table. This is valuable though when performance tuning, as we will show later.

SELECT

object_name(object_id),

alloc_unit_type_desc,

avg_page_space_used_in_percent,

record_count,

min_record_size_in_bytes,

max_record_size_in_bytes

FROM sys.dm_db_index_physical_stats(DB_ID(N'QTuner'), OBJECT_ID(N'dbo.SpanOverFlow'), NULL, NULL , 'DETAILED');

Listing 4

How can Row Overflow affect performance by introducing more pages?

So far, we’ve discussed what the row overflow page is, how it is stored, and when the engine decides it is needed. The question arises; can row overflow pages cause a performance problem by introducing more reads?

When row overflow pages are created, there is a small amount of overhead that will come with them. This is from having to pull from these pages to fulfill requests made of them. However, with proper indexing, the overhead is typically contained to a minimum and other bottlenecks in performance are typically at the front line. However, this brings up a situation in which a normal exercise of tuning by utilizing execution plans can mislead a DBA or Developer into missing a key step in tuning when row overflow pages are involved.

For example, the query in listing 5 shows the creation of a basic table containing a primary key used as the clustered index and 2 more columns that potentially could cause an overflow page to be created.

IF EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.TABLES WHERE TABLE_NAME = 'OverFlowPages')

BEGIN

DROP TABLE OverFlowPages

END

CREATE TABLE OverFlowPages (ID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY,BadUseVarcharOne VARCHAR(5000),BadUseVarcharTwo VARCHAR(5000))

Listing 5

To show what we’ve discussed already regarding when a row overflow page would be created, listing 6 shows an insert into the new table, OverFlowPages, that would not exceed the row limit of 8060 bytes.

INSERT INTO OverFlowPages SELECT REPLICATE('0',5000),REPLICATE('0',3000)

Statsitics IO: Table ‘OverFlowPages’. Scan count 0, logical reads 6, physical reads 0, read-ahead reads 0, lob logical reads 0, lob physical reads 0, lob read-ahead reads 0.

Listing 6

Running the query from Listing 4 reveals the normal and expected in row allocation unit listing. Using listing 3, review the pages and allocation units that exist for the OverFlowPages table.

Further investigation of this table is done by using listing 7. This will insert a row and measure the time in milliseconds to perform the insert, as well as review the statistics of the insert.

DECLARE @STR DATETIME = GETDATE()

INSERT INTO OverFlowPages SELECT REPLICATE('0',5000),REPLICATE('0',3000)

SELECT DATEDIFF(ms,@STR,GETDATE())

Listing 7

The insert results in an average of a 62 millisecond insert time and statistics as shown below.

To see if a performance impact is made by the introduction of an overflow page creation, the code in listing 8 is used to insert into the same table and exceed the 8060 byte maximum.

DECLARE @STR DATETIME = GETDATE()

INSERT INTO OverFlowPages SELECT REPLICATE('0',5000),REPLICATE('0',4000)

SELECT DATEDIFF(ms,@STR,GETDATE())

Listing 8

__

The overall duration is the same even when we exceed the row size and introduce a row overflow page. A further test performing 1000 inserts into the same table reveals no drastic impact to performance. From this we can see the actual inserting of a new row is not impacted greatly. This was only performed to show the minimal impacts during an insert event. But, what happens with this table when a select is performed, as shown in listing 9?

SELECT BadUseVarcharOne FROM OverFlowPages WHERE ID = 1

Listing 9

Table ‘OverFlowPages’. Scan count 0, logical reads 2, physical reads 0, read-ahead reads 0, lob logical reads 0, lob physical reads 0, lob read-ahead reads 0.

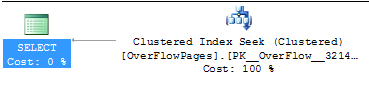

As shown above, the statistics and actual execution plan that were generated from the select statement are optimal. The clustered index was used, as expected, and the query executed as well as it will. However, this was due to the first row (ID of 1) being a previously inserted row that did not exceed 8060 bytes. The inserts from listing 8 did exceed the row limit and the remaining 100 secondary tests that were performed. Will they show the same results? Listing 10 shows a select that is returning a row that has a row overflow page. With our examples, the ID of 50 is selected as it was a known insert that exceeded 8060 bytes.

SELECT BadUseVarcharOne FROM OverFlowPages WHERE ID = 50

Listing 10

Table ‘OverFlowPages’. Scan count 0, logical reads 2, physical reads 0, read-ahead reads 0, lob logical reads 1, lob physical reads 0, lob read-ahead reads 0.

In the results from querying a row that does have a row overflow page, the execution plan is still an index seek, but the statistics show a slightly different result. There is now an introduction of a lob logical read in order to fulfill the request to bring in the row overflow page that is found by the pointer in the index page. The introduction of the lob logical read will affect performance in a negative way by increasing resource utilization. This would be more evident when a select statement required returning several rows, even when the index seek on the clustered index is performed, but multiple lob logical reads were needed. In this case the execution plan is performing the seek that is needed but bringing in more pages than required to fulfill the needs.

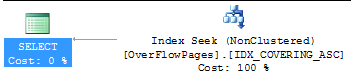

Reducing the IO for this situation is usually done before the situation arises with the database and table design process. In a lot of cases, normalization would have greatly affected the overall width of tables as well as knowing wider tables could cause overall performance problems. However, in many cases, the wide tables are a necessity and do exist. The problem still exists in tuning the select statement from listing 10. In this case, the plan is already in a graphical state that would be ideal. However, the statistics show the problem that exists with the lob logical reads. Given the query in listing 12, a covering index could also generate an execution plan that would be optimal. Run the code in listing 11 to create a covering index for the query in listing 10.

CREATE NONCLUSTERED INDEX IDX_COVERING_ASC ON OverFlowPages (ID) INCLUDE (BadUseVarcharOne)

Listing 11

__

SELECT BadUseVarcharOne FROM OverFlowPages WHERE ID = 50

Listing 12

__

Table ‘OverFlowPages’. Scan count 0, logical reads 2, physical reads 0, read-ahead reads 0, lob logical reads 0, lob physical reads 0, lob read-ahead reads 0.

The above execution plan shows the covering index now being used as well as the removal of the lob logical reads. In this case, the query was successfully tuned for a better execution plan. Further testing on overall execution time had an average of 320 milliseconds using the new covering index and an average of 400 milliseconds relying on the clustered index and lob logical reads thus, more pages into memory.

This was a specific situation and query given a fairly basic table. In the case of selectivity and specifically querying on one ID as shown in listing 10, the optimizer will be more selective on the clustered index. In this case an index hint may be more effective in order to force the use of the covering index or more appropriate nonclustered index as shown in listing 13.

SELECT BadUseVarcharOne FROM OverFlowPages WITH (INDEX=IDX_COVERING_ASC) WHERE ID = 50

Listing 14

Other variations may occur where this tuning effort is not effective, such as a return that would contain multiple columns that exceed the limits. For example, if the covering index was only effective if the nonkey columns required BadUseVarcharOne and BadUserVarcharTwo, the use of the nonclustered index would still show a statistics IO with the lob logical reads. This is an overhead that would be required. Assuring the returned columns in this case or the joining columns in other queries would be something to look into for removing them or altering them.

Summary

Row Overflow Pages are a way for the engine to handle a table and columns being greater than the normal 8060 byte row limits when variable length data types are used. Tables are still required to abide by the 8000 limitations for a data type as well as a fixed length row exceeding 8060, but this feature with variable length data types is useful. Although row overflow pages can prevent certain table designs, good table design and normalization when a table changes often should not be forgone simply because the ability exists to exceed the 8060 byte row limit. When the situation does present itself, ensure steps are taken to check statistics IO on what the actual execution plan is generating when row overflow pages are introduced, to limit the reads that are occurring. Indexing is the single most effective method in altering performance in a positive and negative way in SQL Server databases. Ensuring covering indexes are created and index strategies that pull only the required data will propel even indexing to a level that should be sought after in all performance tuning practices. Be sure to expand all options and index structures in order to generate the most beneficial index possible. __