Scalability is easy, provided you don’t need it to work.

Probably the number one failure of system scaling is when people dive right in and start building. No baselines, limited measurements, no analysis, just a hypothesis and a whole lot of late nights tweaking the system. With extra complexity comes extra costs, from the initial development through more expensive maintenance. Scale poorly and not only do we take on those extra complexity costs, but also the more obvious additional costs of the actual implementation (new servers, more resources, etc).

The Somewhat Contrived Example

Recently I’ve been working on a system to simulate parallelizing workloads, specifically workloads that depend on external resources with rate or load thresholds. Let’s use it to look at a somewhat contrived example.

So the backstory is that I have a batch process that is running more and more slowly as we take on larger and more frequent workloads.

I start by testing the batch process locally so I can see how slow it is before I make changes.

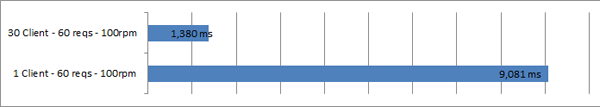

1 Client, 60 Requests, 100rpm

Locally it runs pretty quickly, but I’m betting that parallelizing the process will give me a significant increase in speed.

1 Client vs 30 Clients, 60 Requests, 100rpm

Look how well that performance improved, I achieved better than a 6x improvement in performance. My job here is done.

Except when I try to push this to production, I start getting a lot of errors.

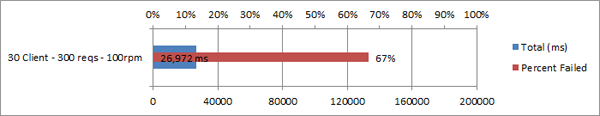

30 Clients, 300 Requests, 100rpm – 67% Failure Rate

As it turns out, the external API my process saves the data to has a rate limit. When I exceed the allowable rate, I’m throttled for a short period of time. Any requests I make during that throttle period are returned with errors indicating I’m throttled.

Hmm. Luckily there are a number of common patterns available to retry these types of failures. I’ll add an exponential back-off retry pattern so that when I get throttled my service will retry failed requests at slower rates until the service un-throttles me. While I’ve found plenty of code examples online, none of them seem to have recommendations, so I’ll just use one of the sample settings they provide.

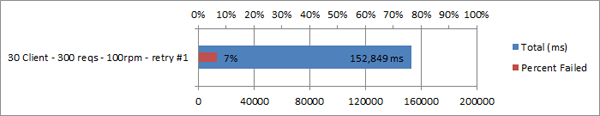

30 Clients, 300 Requests, 100rpm, Retry Policy #1 – 7% Failure Rate

Hmm, better. My failure rate has gone way down. What if I tweak the values?

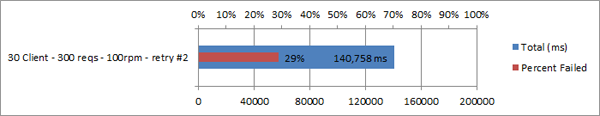

30 Clients, 300 Requests, 100rpm, Retry Policy #2 – 29% Failure Rate

Oh, that was bad, I obviously was on the right track before. What if I just extend the retry amount a bit to try and knock out the last bit of errors.

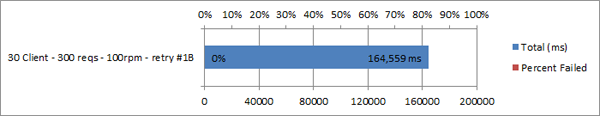

30 Clients, 300 Requests, 100rpm, Retry Policy #1B – 0% Failure Rate

Ok, perfect. Now I have a system that is more than 6 times faster than the original, can be easily extended by throwing more workers at it, and is actually in a better position to handle occasional slow downs from my 3rd-party service.

Success!

Where I Went Wrong

Ok, so maybe not. Over the course of my little story I went wrong in a number of places. Even though this was a contrived example, I’ve watched very similar scenarios play out in a number of different organizations with real systems.

The Bottleneck

The first and most critical problem was that I didn’t actually locate the bottleneck in my process, I simply tried to do more of the same. The Theory of Constraints tells us that we can improve the rate of a process by identifying and exploiting the constraints.

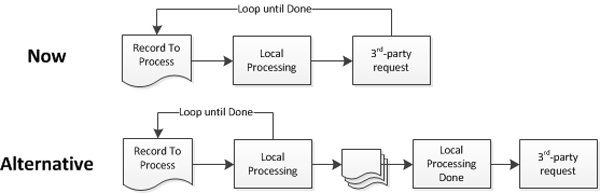

In this system, the constraint looked like it was the sequential execution of the tasks, but in reality the constraint was the time it took to call the 3rd-party API. Had we identified that bottleneck before starting, we could have approached the problem differently.

Process – Alternative Design

Rather than the parallel complexity, we can modify how the tasks are executed to try and take advantage of knowing where our bottleneck is. If the API allowed us to submit several requests in a batch, this redesign would net us several orders of magnitude improvement. Another option would be to run the results of the local processing into a queue and submit requests from there at a slow trickle, using only a percentage of our API limit so as not to disrupt any other real-time operations or batch processing the system supports. Another option we could take advantage of is not starting any of our expensive 3rd-party communications until we know that the entire job can actually be processed successfully through our local process.

Identifying the constraint unlocks the ability to turn the problem on it’s head and achieve higher improvements, typically by orders of magnitude.

The Math Error

I concluded the scenario above by assuming I had found a good solution that also had a lot of headroom. Unfortunately what I actually did was find the ceiling. I have tuned the retry policy to 30 parallel systems, increasing that number could easily destabilize it further and cause more errors or delays. The headroom is, in fact, an illusion.

The Evolving Assumption

Somewhere along the way I found 30 clients to be a great improvement and didn’t test other options. Then I made some assumptions about a retry policy. Then I tweaked that retry policy until the error rate disappeared. My assumptions made sense at the time, so I never questioned where they were leading me.

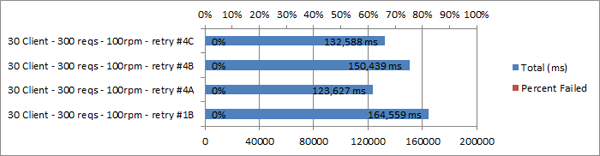

When I found a winning combination for my retry rate, I didn’t realize I was missing other, better options:

30 Clients, 300 Requests, 100rpm, Retry Policy #1B vs 4A-C

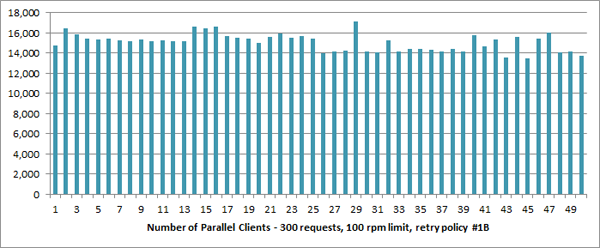

What’s worse, is that trail of assumptions along the way was never re-validated. I concluded with a 6.5x improvement, but is that still accurate?

1-50 Clients, 300 Requests, 100rpm, Retry Policy #1B

When I run the same settings on a range of 1 to 50 clients, we can see that I lost that original 6x improvement along the way. All I have managed to do is add complexity and some very explicit costs for those additional systems.

Note: What happened to retry policy #3? Well originally 1B was actually named 3, then I decided to update the name halfway through the post but was too lazy to update all of the completed images. Oh well.

Scaling the Wrong Thing

This post used fairly small numbers, had I applied a larger workload, higher throughput rates, different throttling windows, the whole problem would have turned out differently.

When we set out to make a system scale, we need to identify the real scenarios we are trying to scale for and the bottlenecks that stand in our way. Blindly performance tuning can look like an improvement, but is really just a poor short term investment that often entrenches the current performance problems even more deeply. There are a lot of questions that should be asked about the intended result, responsiveness fo the system, other operations it has to support while under load, potential overlap of that load, the type of load, etc. The patterns for one system may have relevance for another, but could just as easily be completely incorrect.

How hard it is to scale a system is going to depend on a lot of factors. Getting it wrong just happens to be the easiest option.

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.

My roles have included accidental DBA, lone developer, systems architect, team lead, VP of Engineering, and general troublemaker. On the technical front I work in web development, distributed systems, test automation, and devop-sy areas like delivery pipelines and integration of all the auditable things.